Restoring humanness: reflections from my first DIEP flap

- John Winton

- Mar 30, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2025

What is a surgeon’s calling? I stood in the operating room in my operating room shoes. I had woken up to my alarm at 5:15 — a time when others my age might just be returning home. I was early enough to score a free daylong parking spot near the hospital, the equivalent to winning the lottery in San Francisco.

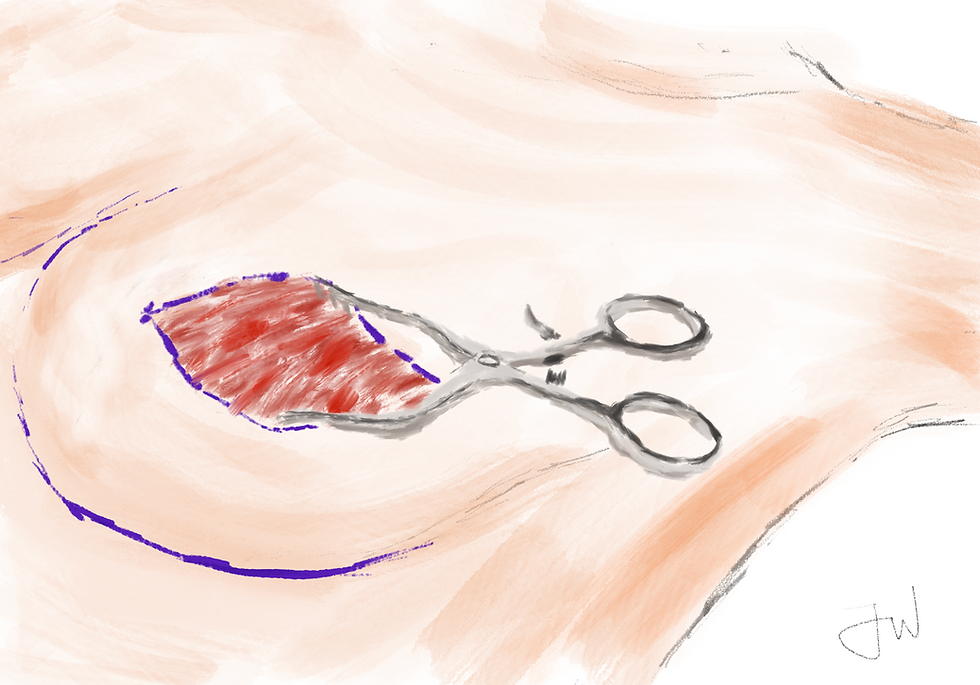

Now here I stood overlooking a patient who likely did not sleep well last night, but was now deep asleep on the OR table. The purple marks on her abdomen and chest told the story of a long procedure. A double mastectomy with skin sparing, oophorectomies, and bilateral DIEP reconstruction — the reason I was there.

I had only ever shadowed three procedures before today, of which the longest might have been two hours. I almost saw this lengthy DIEP flap procedure as a test: Was I really interested? Did I truly want to be a surgeon? Could I even stand for that long? However, as the minutes rolled into hours, I remained captivated by the handiwork of my plastic surgery mentor and his two residents.

To see a procedure that I had read about in books and papers for the last two years was truly special. The work bordered on magic. Crafting new, healthy breasts in the place of diseased tissue seems almost fantastical. Before Hippocrates drove medicine away from divinity, the Greeks believed in the power of deities to bestow healing through the works of a doctor. Temples to Asclepius were the first hospitals. However, two millennia of evidenced-based research pushed science and medicine away from religion; so far, in fact, that science and religion were often at odds with each other.

Still, I now found myself standing in a modern day temple of sorts. It was a temple of science, and I was surrounded not by statues of a Greek god with his serpent and staff, but by Bovie machines and Bair Huggers. In my head, I saw the same miracle work that ancient men attributed to Asclepius.

Is that a reconstructive surgeon’s role? To restore humanity to God’s image? I don’t believe in the same gods as the Greeks did, but as a Christian, I could stand behind that.

I must credit my mentor, Dr. Rose. He welcomed me into the miracle-working team. More than an observing student, I was also a contributor in my own small way. Despite his son’s evening talent show motivating him to finish earlier, Dr. Rose graciously allowed my inexperience to slow him down ever so slightly. He handed me the retractors, the stapler, the suture scissors, and the flap.

Perhaps you, like myself, did a double take on the last one. Entrusting a not-even-medical-student with the viability of the entire operation’s focus seemed quite risky. “Be careful,” he told me as he cut the remainder of the flap away from the body. Even slightly excessive tension in the focal vessels could jeopardize the entire flap, Dr. Rose explained.

Don’t drop the flap. Don’t drop the flap. I thought of my younger self dropping his fresh bagel in the car. Or when he dropped his church backpack while crossing the street. Or when he dropped his ice cream before his father had finished paying. Don’t drop the flap. When I studied my first procedure in the OR, Dr. Rose told me, “if you’re helping, you’re part of the team. If you’re not helping, you’re part of the disease.” True, he was joking, but I was trying my very best not to be part of the disease this time.

Needless to say, everything went well. The eight hour procedure maintained my attention, signaling continued interest in this career path. My new shoes kept my feet happy. My mentor was able to listen to his son’s piano at the talent show. The patient left with two new breasts and a tighter stomach.

Was that a plastic surgeon’s purpose? New boobs? Most people would say yes. Some surgeons would agree. Interestingly, for a specialty with some of the most visible results, I would argue that people have some of the most difficult time identifying the surgeon’s true contributions. Likely, the former causes the latter.

The patient recovering from her surgery surely did not see this procedure like that. If she had her way, she likely would have never spoken to a plastic surgeon in her life. True, success in the operation did not mean a life saved. Neither did failure mean a life taken. We weren’t performing cardiac surgery. But maybe it meant new life for the patient.

My grandmother had breast cancer twice, separated by over a decade, and each time remedied by a minor lumpectomy. Among breast cancer patients, she would be considered luckier than most. She knew she would go home with her body intact. Reconstruction of the breasts by methods such as the DIEP flap offers a restoration of one of the most uniquely female characteristics. After all, there is a reason why gender-affirming surgeries often involve mastectomies. Breasts are crucially linked to female identity.

In my eyes, that was why the plastic surgeon was there. The purple drawings on the skin showed a meticulous effort to preserve a patient’s dignity in womanhood, drawing both from artistic, visual beauty and anatomical and surgical knowledge. The patient left the hospital free from the tribulations of cancer, and she did not have to sacrifice her identity for it.

Plastic surgeons are the manipulators of the body, crafting new from old and form from disunity in a method so uniquely creative among healthcare fields. Genesis 1:27 says, “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (NIV). A plastic surgeon’s job then, like any other doctor, is not only to restore humanness, but to restore divinity that God has placed in each of us.

I could not imagine many tasks nobler than that.

Comments